I have two huge passions: worldviews, and stories. Worldview is the set of beliefs guiding what we value and how we interpret our world. A large part of my worldview is Christianity. I believe God the Son became a man, lived without ever sinning (something no one else ever did), died a criminal’s death on a cross as a sacrifice to pay for our sins, and rose from death three days later, proving His sacrifice sufficient. It’s important to me to share my worldview, but I’m also fascinated by others’ worldviews and how they affect their understanding of life.

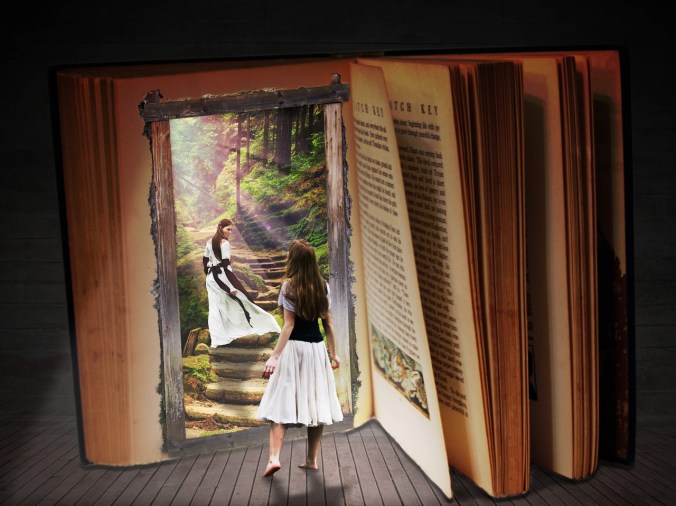

Culture often tells us discussions about worldview can be unpleasant or unsafe. This is why money, politics, and religion are often taboo subjects until we know each other well. Such familiarity and trust are rare among people with different worldviews; we gravitate toward those like us. Stories offer a safe way to investigate and share worldviews. We get into someone else’s head, see life through their eyes, and feel entertained. This can prepare us to interact with people of similar worldviews in the real world.

We can’t escape stories. Close your book, and there are stories on TV. Cut your cable, and there are stories on the Internet. Discontinue your service and there are stories in the weekly paper. Cancel your subscription, and your coworker tells stories in the next cubicle. Stories are a basic form of communication. Why?

Of all creation, only humans are known to tell stories; billions of creatures thrive without them. Stories are entertainment, not survival. Why do all of us enjoy them, regardless of culture? I believe God designed story to point us back to Him.

Humans, according to the Bible, have fallen from our perfect relationship with God. We are broken, our sinful hearts distorting our view of the world. Broken people are one of the most common elements in story. Our stories typically follow someone who wants (lacks) something. They set out, sometimes in the wrong direction, to fill a need.

Our stories let us examine this issue from many angles. What happens if our hero never finds what he wants? What if he does? Is that necessarily better? What will it take to get him there? If the hero is content wherever he winds up, a better person through the trials he’s faced to get there, the story ends happily.

What makes a “better” person? “Better” essentially means “more like God.” According to Scripture, God never had a beginning (Psalm 90:2). Everything else does. God preexists everything, and everything exists because God created it. God is the original and highest good, the standard by which we judge the goodness of everything else. He is perfection itself, and if anything is going to be “more perfect,” it must be more like God.

So, at the beginning of a story, we meet a broken hero who braves trials to become more like God. He tries this and that to accomplish his goal, but doesn’t find his way until he comes to the end of himself. Only when he dies to his old self can he overcome his greatest obstacle.

What I’m describing is Joseph Campbell’s “monomyth,” a pattern he saw running through stories from various ancient cultures and explained in The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Campbell saw the Bible as only an example of this pattern. I’m suggesting our stories match the Bible’s pattern because God has given us an innate desire to pursue Him in His way.

Some stories aren’t about a broken man, but about the only whole man in a broken society. He sticks out like a sore thumb, his very existence a reproach to those challenging him to be like them. He may be persecuted by society or sacrifice himself to rescue them, depending on the story. Maybe some recognize he was right and follow his example.

Sound familiar? It’s the same story I told in the first paragraph, told in the four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) in the Bible. Jesus was misunderstood, persecuted, and eventually killed for His perfectly righteous example. After His resurrection and ascension into Heaven, His followers, Christians like me, try imperfectly to follow His example. Stories like this speak to us because we’re made to follow a perfect Savior.

Finally, some stories — tragedies — are about people who end up broken. Perhaps they’re about what happens when we won’t sacrifice what’s holding us back. People remain broken because they don’t pursue God and become better. Perhaps their message is that this is life’s true nature. Even these dismal stories can draw us to God by showing us how distasteful that idea is to us.

Why are these stories so depressing? We’re made to pursue God. We’re made to take joy in Him, not evil. Those who seem to take joy in evil often enjoy the power or pleasure it promises. Power and pleasure are godly attributes that ought to attract us to Him. The serpent of Genesis 3 tempted man to rebel against God by offering a godly attribute, wisdom, and telling Adam and Eve they could have it without God. When we ignore God and pursue His attributes in ungodly ways, evil results.

Evil is the word for when good is twisted. Where we see evil, we see the twisted remains of something designed to glorify God. Evil can’t exist in a vacuum; when there is no good to be twisted, evil doesn’t exist.

In tragedies, something about the world is broken at the story’s end. It’s worth asking what’s broken and why we think so. What would the world look like if it weren’t broken? Why would that be better? It’s also worth asking whose efforts broke the world, and what they were pursuing when they did so. Were they pursuing something good, but ignoring God?

On Worlds Viewed, I want to discuss what specific stories from books, movies, games, the news, and other media have to say about God’s glory. Many stories counter biblical truth but rely on themes and images that get their value from God’s existence. Guided by Scripture, I want to look at why these themes have universal appeal, and how we find meaning through someone else’s adventure.

I hope you will share your own thoughts and opinions in the comments. Each of us may see the same media but come away with a different story thanks to our unique perspective. I’d love to hear yours.